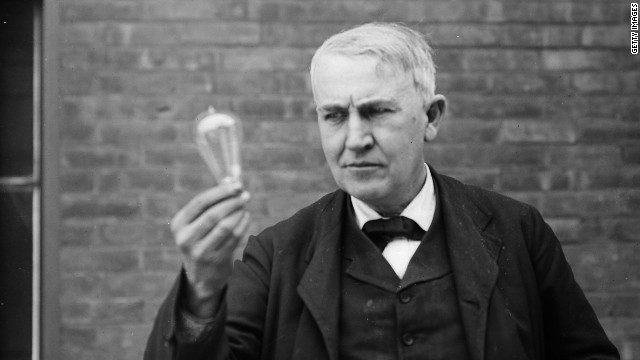

There are moments when the world changes in an instant…and one of them came 135 years ago, when Thomas Edison drove out the darkness that had haunted human dreams from time immemorial. With the flick of a switch, Edison pierced the night with the first public demonstration of the incandescent light bulb. It fittingly happened on the very last day of the 1870s, on December 31, 1879. It would be the last decade of human history lived in the dark.

Edison was already famous by 1879, already dubbed “The Wizard of Menlo Park” for his amazing invention of the phonograph two years earlier. Now he claimed to have solved a puzzle that had been stumping inventors throughout the 19th century…the riddle of producing electric light, and doing so in a way that was practical for widespread use. Early attempts had been ongoing since at least 1802, but they were all plagued with problems. They burnt out too quickly, cost too much to make, or drew too much current to be practical.

Edison had fiddled with the problem, using different materials to produce light. He settled on a carbon filament that would last for 1,200 hours. After successfully testing the bulb earlier in the year, he arranged a New Year’s Eve demo in 1879 where he would light up a street in Menlo Park, New Jersey. There was so much excitement that the railroads ran special trains to Menlo Park just for the occasion.

After Edison’s successful demo, the age of the light bulb came quickly, at least to the cities. Edison and his crew outfitted the steamship Columbia with electric lights the following year. By 1882, he had set up New York’s first electrical power plant on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan, and switched on a steam-generating power station in London. By 1887, Edison had 121 power stations in the United States. He said "We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles."

Edison achieved his goals with efficiency, and no short streak of ruthlessness. He vehemently campaigned against the use of AC (alternating current) electrical systems, which had been developed with the work of his former employee-turned-rival Nikolas Tesla, in favor of his own DC (direct current) distribution system. He told the public AC was more dangerous, and helped develop the electric chair using AC to back up his point. His employees electrocuted stray animals using AC to demonstrate its lethality. (The fact that all electrical currents are potentially dangerous was glossed over for a public still coming to grips with electricity.)

While rightly celebrated for his genius as an inventor, Edison was also powered by the instincts of business and showmanship. He hired men with the mathematical know-how to put his intuitions into practice, and then reaped public glory for the teamwork being produced at Menlo Park…sort of the Walt Disney of inventing. But that application of large-scale industrial processes to science was itself part of his genius, and helped him earn his reputation as one of the greatest inventors of all time. When he died in 1931 at age 84, he held 1,093 U.S. patents…and it is impossible to imagine modern life without the innovations he helped develop, like recorded sound and motion pictures. But most of all, Edison cast his glow on all of us when he ushered in the 1880s, and a new world…when he let there be light.

|

| http://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnn/dam/assets/111230100454-sloane-edison-story-top.jpg |