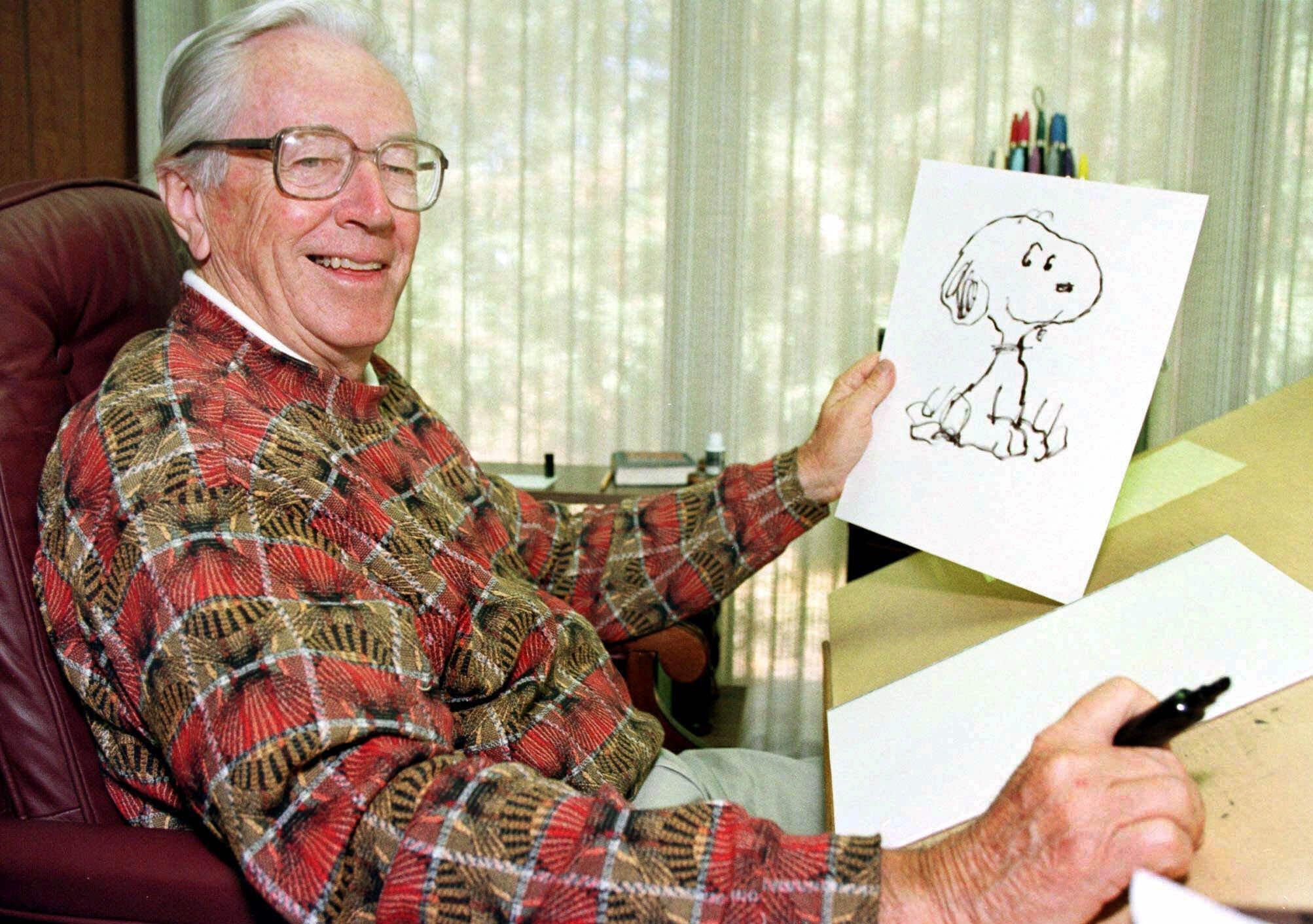

When Charles M. Schulz (born in Minneapolis 92 years ago on November 26, 1922) tried to submit some of his drawings for the yearbook at his high school in St. Paul, he was turned down. Many years later, the school atoned for this mistake by erecting a 5-foot-tall Snoopy statue in the main office.

Schulz seemed to draw widely on his own life in writing and illustrating the life of his luckless hero Charlie Brown. His unrequited love for the Little Red-Haired Girl was based on an accountant Schulz had been smitten with at art school and unsuccessfully proposed to. His family dog as a child resembled Snoopy. Even Charlie Brown’s absurd failures seemed to find precedent in his life. Schulz saw combat toward the end of World War II, but claimed that on the one occasion he had a chance to fire his machine gun, he forgot to load it. (What could have been a fatal mistake turned out OK, when the German he was targeting compounded the absurdity of the story by surrendering anyway.)

In 1950, Schulz landed a syndication deal for a feature he had conceived as a single panel called “Li’l Folks.” The syndicate preferred to run it as a four-panel strip and called it “Peanuts.” Schulz wrote and drew the strip for almost 50 years. It made him a rich man, but he only took one vacation during the strip’s run, a five-week break to celebrate his 75th birthday.

Declining health forced Schulz to retire from “Peanuts” in December 1999. He died just two months later, of complications from colon cancer, at age 77. The final original “Peanuts” strip ran the next day. Schulz had predicted the strip would outlive him, due to the long turnaround time between drawing and publication. In a literal sense, he was right by 24 hours. But “Peanuts” didn’t end with Schulz, although he asked not to be replaced on the strip, to preserve its authenticity. The syndicate has respected his wishes, and since his death, “Peanuts” has been in “reruns,” drawing on the 50 years of material Schulz left behind.

The popularity of “Peanuts” can be analyzed in many ways, but Bill Watterson (of “Calvin and Hobbes” fame), who claimed Schulz as an inspiration, praised it for its “unflinching emotional honesty” and “serious treatment of children.” Charlie Brown never kicked the football, however much fans asked for it. Schulz took life’s constant failures and made them enjoyable…an object lesson in the art of “good grief.”

No comments:

Post a Comment