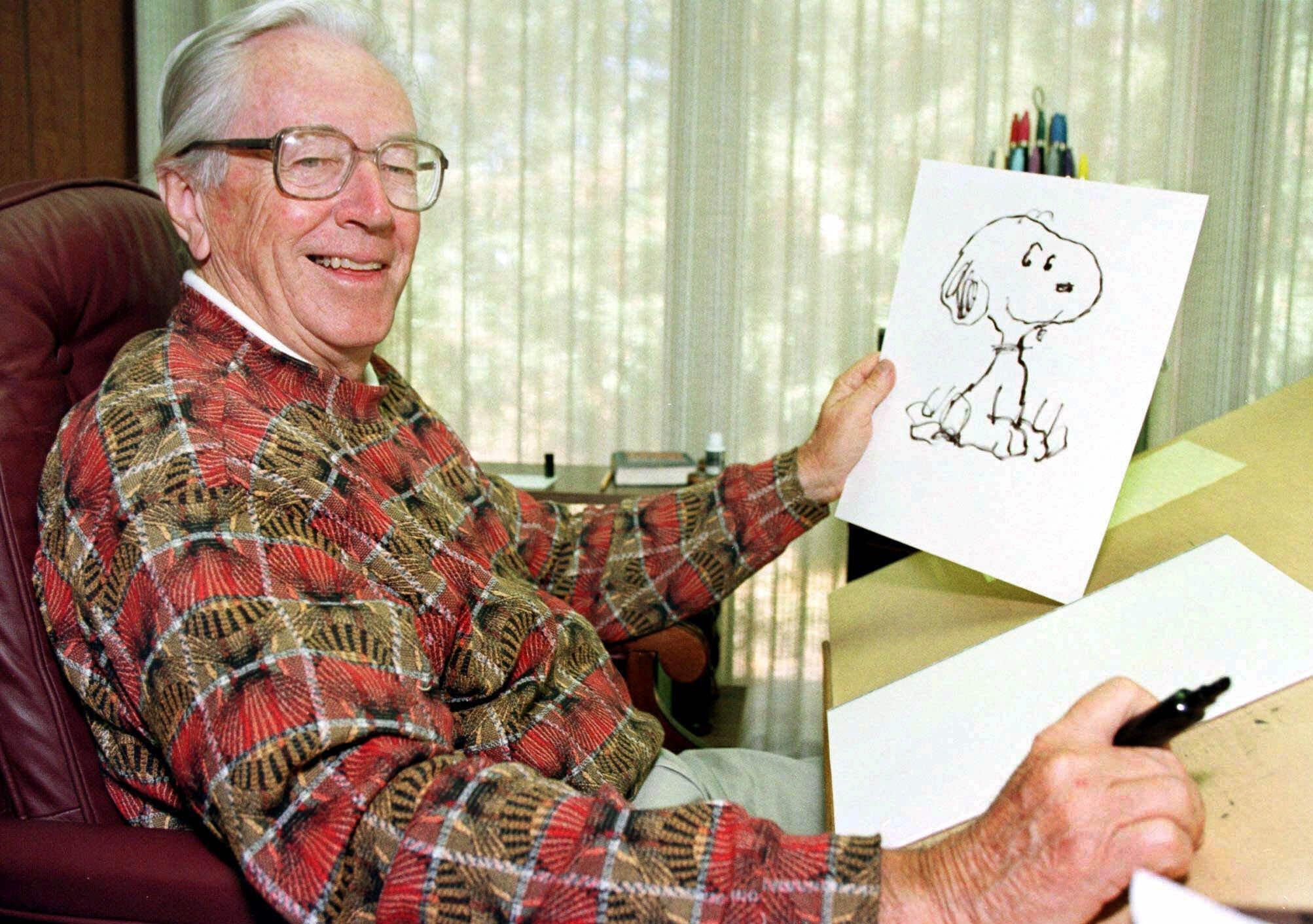

Two titans of history shared birthdays on this date. Mark Twain was born Samuel L. Clemens in rural Missouri 179 years ago on November 30, 1835. Winston Churchill entered the world in the English town of Woodstock 39 years later on November 30, 1874. You can judge for yourself whose life was more influential.

Twain’s writings and lectures chronicled American life in the late 19th century, while slaughtering its sacred cows with a wit that was at once gentle, welcoming, and deeply cutting. His “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is seen by many as the “Great American Novel,” and while its use of unvarnished racist language common to its time makes it a hard read today, it was a brilliant send-up of the hypocrisy of a country that mixed religion and slavery into one unsavory stew. (Huck Finn’s declaration to himself of “All right then, I’ll go to hell” upon deciding to ignore the warnings of every preacher he had encountered by helping the slave Jim run away is one of the most arresting passages in literature.)

Across the Atlantic, and a few decades later, Churchill overcame early failures in British military politics to rise to power as the steady and dogged English prime minister during World War II. At the height of Europe’s confrontation with the Nazi menace, Churchill’s calmly confrontational leadership style was seen as the perfect tonic for a country whose politicians had unsuccessfully sought to placate Hitler. In distinctive English style, however, the voters threw him out of office after the war…not necessarily out of dissatisfaction, but because maintaining the peace was seen as a different kind of job, requiring a different type of man, than winning the war had been.

One thing both men shared was a love of the written word, and an appreciation for serious ideas. (Churchill was a noted historian in addition to his political achievements.) While separated by almost four decades, they were contemporaries, and their periods of fame overlapped around the turn of the 20th century, when Twain was an aging celebrity and Churchill was a rising star in British public affairs. They met on at least one occasion in 1900, when a 65-year-old Twain introduced a 26-year-old Churchill at a speech in the ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria in New York. In his introduction, Twain gently poked Churchill for his support of England’s Boer War in South Africa, at the same time America was tangled up in war in the Philippines. Twain said the two countries were “kin in blood, kin in religion, kin in representative government, kin in ideals, kin in just and lofty purposes; and now we are kin in sin.”

Another thing Churchill and Twain shared: They both are credited with dishing out some truly epic insults. To give just one example from each, Twain is credited with this beauty: “I did not attend his funeral, but I sent a nice letter saying I approved of it.” Churchill is said to have responded to a woman who accused him of being “disgustingly drunk” by saying “My dear, you are ugly, but tomorrow I shall be sober and you will still be ugly.”

|

| http://infinityinsurance.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/WinstonChurchill_MarkTwain.jpg |