Lincoln spent the day at Cooper Union, a private college in Manhattan’s East Village where he delivered a lengthy 7,000-word address carefully detailing his position on slavery. Lincoln labored at length to justify his position against its expansion into Western territories that were preparing for statehood, aligning his position with those of the Founding Fathers. This speech has been overshadowed since, for good reasons. Lincoln is making a tepid, conservative case against slavery’s expansion, far less inspiring than the abolitionist stances he ended up taking as a result of the Civil War.

But if modern audiences find little of interest in the speech, Lincoln’s intended audience was very impressed. Lincoln was a man from the frontier known for telling jokes. He had made a name for himself in Illinois by debating Stephen Douglas during the Senate campaign of 1858. But Lincoln’s careful argumentation on this stage – “informed by history, suffused with moral certainty, and marked by lawyerly precision,” one Lincoln scholar said – helped transform him from regional curiosity to a national leader. It didn’t hurt that the speech was given in New York, the nation’s media capital. The speech was reprinted in newspapers and pamphlets across the North, and has been seen as the crucial piece in helping Lincoln gain the 1860 nomination for president of the young Republican Party that May.

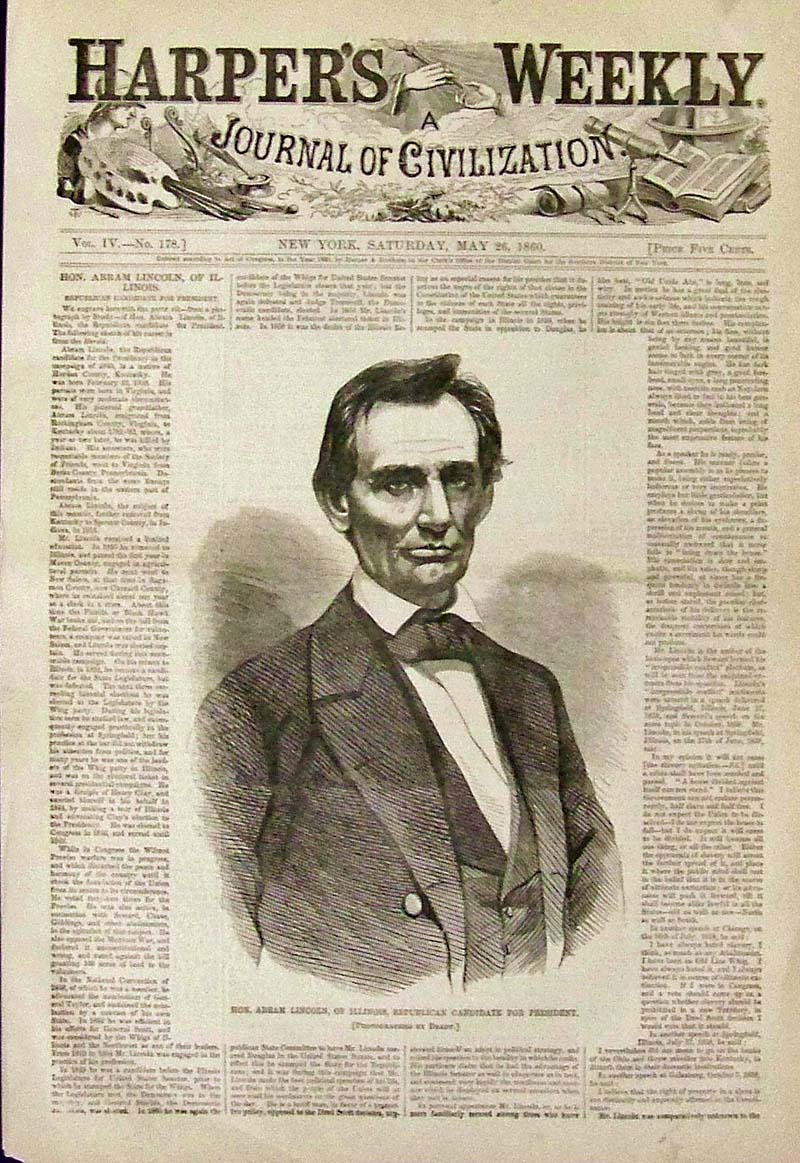

A few hours before the speech, Lincoln made another stop – at the photography studio of Matthew Brady, remembered today for his stirring photographs of Civil War battlefields. Lincoln called on Brady for a portrait. Photography was still a young medium, and Brady’s picture of a beardless Lincoln provided the perfect visual counterpoint for Lincoln’s successful speech. After he won the nomination, Harper’s Weekly used the portrait to make a triumphant front-page engraving of the nominee (erroneously captioned as the “Hon. Abram Lincoln”). In 1860, simply seeing a candidate look presidential had value in itself…particularly for Lincoln, who was described as being so gangly and thin by his opponents that a humanizing picture was worth a thousand words. Or as Lincoln said later, the picture allowed him to display a “human aspect and dignified bearing” to offset his opponents’ descriptions of him. (Could simply proving you look human be enough to swing an election?)

The tides of politics are tricky to discern. Lincoln towers over our national consciousness today, but the fact is he had to win election in a system just as dominated by its channels of communication as we have today. Could a speech and a photograph really swing an election? Lincoln seemed to think so, when he was quoted as saying “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me president.” Of course, knowing Lincoln, this could have been intended as a wry comment on the outsize importance one day’s events could have on a whole campaign. But whether it was said earnestly or facetiously, there was certainly some truth to it.

|

| http://www.printsoldandrare.com/lincoln/103linc.jpg |

No comments:

Post a Comment